As a veteran public health worker, Chantee Mack knew the coronavirus could kill. She already faced health challenges and didn’t want to take any chances during the pandemic. So she asked — twice — for permission to work from home.

She was deemed essential and told no.

Eight weeks later, she was dead.

Mack, a 44-year-old disease intervention specialist, lost her life this spring after COVID-19 struck the Prince George’s County Health Department in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C. The coronavirus infected at least 20 department employees, some of whom had attended a staff meeting where they sat close together, union leaders said.

The spread of COVID-19 underscores the stark dangers facing the nation’s public health army — the very people charged with leading the pandemic response.

“We’re the ones called to the fire to do this during an emergency. We are essential. People don’t look at us as first responders, but we are,” said Mack’s co-worker Rhonda Wallace, leader of a local branch of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees who, like other union members, stressed she wasn’t speaking for the health department.

Such outbreaks are a grim threat facing overburdened and underfunded health departments across the nation. An ongoing Associated Press-KHN investigation found that public health spending per person fell 16% from 2010 to 2018 nationally when adjusted for inflation — and 17% in Maryland.

Public health workers in other states, including Ohio, Oregon, California and Georgia, have also contracted the coronavirus, and in some cases even worked throughout their sickness to address the ongoing pandemic. But the Prince George’s department outbreak was among the worst — and occurred as workers dealt with a community caseload that eventually reached over 21,000, more than any other county in Maryland.

Department leaders declined to answer specific questions, citing health privacy laws. Instead, county health officer Dr. Ernest Carter said in a statement they were heartbroken over the loss of a valued employee who had worked there since 2001.

“She was a dedicated public health professional who made a difference in the health and well-being of Prince Georgians,” the statement said.

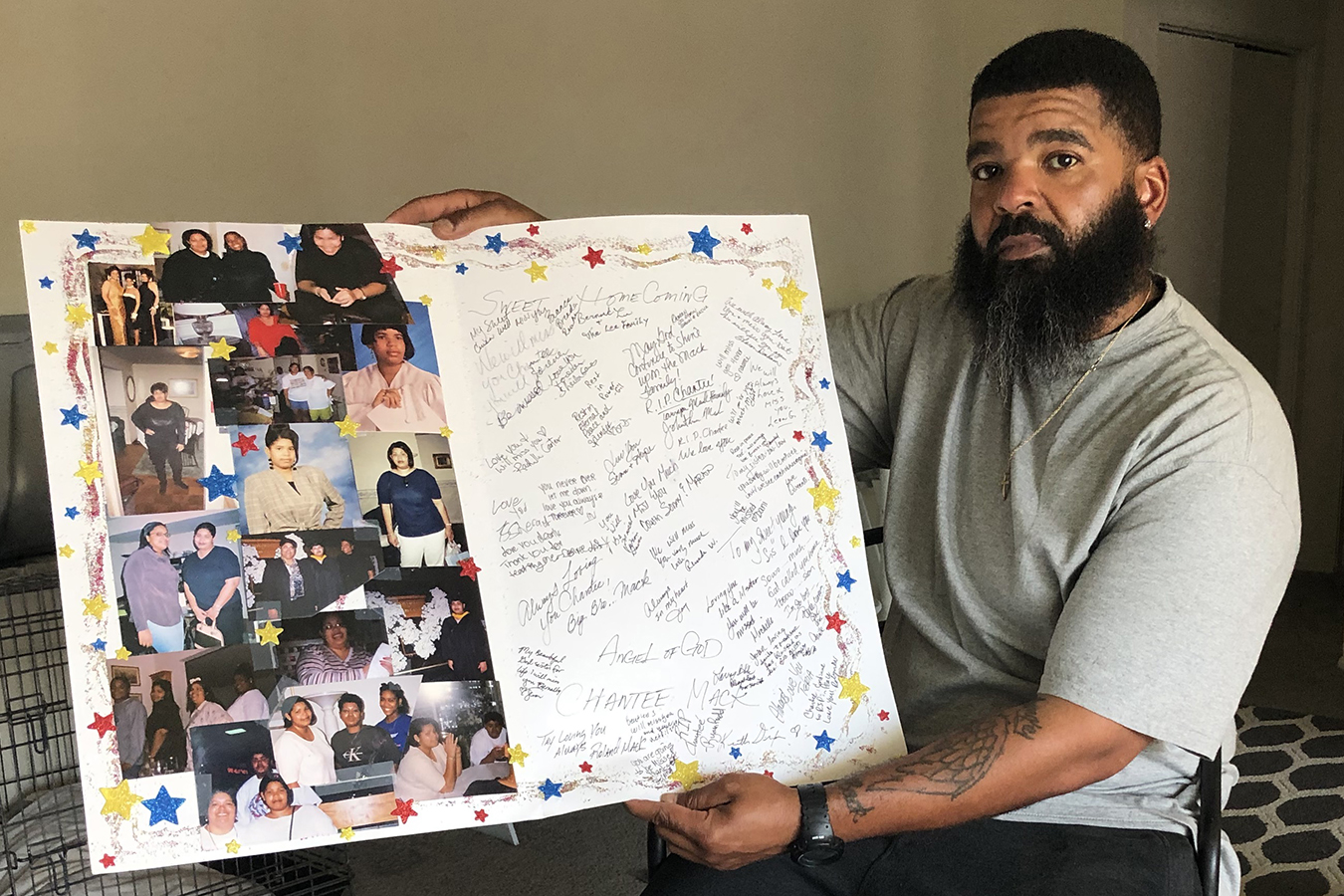

Roland Mack holds a poster with pictures and messages made by family members in memory of his sister, Chantee Mack, in District Heights, Maryland, on Friday, June 19, 2020. The Prince George’s County, Maryland, public health worker died of COVID-19 after, family and co-workers believe, she and several colleagues contracted the disease in their office.(AP Photo/Federica Narancio)

In the pandemic’s early days, department leaders said, they followed a countywide policy on telework devised in 2016, not one developed for the coronavirus threat. At the same time, some employees said, the department failed to provide enough personal protective equipment to keep workers and those they encountered safe — all this in an agency helping shepherd the community through the worst health crisis in a century.

Prince George’s officials did not respond to questions about how the employee illnesses affected the department’s operations. But Dr. Sandra Elizabeth Ford, district health director for Georgia’s DeKalb County Board of Health, said her department, which has lost funding and staff over the years, had to shorten hours when four workers contracted COVID-19 and others had to quarantine.

Ford, president-elect of the board of directors for the National Association of County and City Health Officials, said the need to protect employees and the community weighs heavily on the nation’s health department directors.

“It’s just so many difficult decisions,” she said. “We’re looked at for guidance by everyone — the business community, the schools. We’re learning as we go along.”

Stalked by a Virus

Mack worked in the county’s sexually transmitted diseases program, where one of her jobs was to tell people the results of their tests for infections like HIV, gonorrhea and syphilis. Though she didn’t work on COVID-19, she was among the 100 staffers deemed essential during the pandemic out of the more than 500-employee health department.

In mid-March, the county executive sent an email saying employees should be evaluated to see if they should telework.

Within days, Mack asked to work from home.

So did her colleague Candace Young, another disease intervention specialist and union member who was nine months pregnant.

Young said management rejected her request to telework for five days a week just before her maternity leave began, but approved three days a week.

Prince George’s County Health Department employee Chantee Mack (right) did not work on the county’s pandemic response, but she was deemed an essential employee for her work on sexually transmitted diseases. She was denied permission twice this spring to work from home. She contracted the virus amid an outbreak at the department and died in May. Her brother Roland Mack (left) says he can’t understand why her requests were denied, given that her work consisted mainly of paperwork, computer work and phone calls.(Courtesy of Roland Mack)

Meanwhile, both of Mack’s requests were supported by her immediate supervisors but rejected by upper management, according to union documents. Her brother Roland Mack, 38, said he can’t understand why, since her duties involved mostly paperwork, computer work and phone calls; back problems made it too difficult for her to work face-to-face with clients.

The department’s telework policy considers, among other things, an employee’s responsibilities and work history. In a managers’ conference call, recounted in an internal union document obtained by KHN, Diane Young, associate director, said all family health services’ workers were essential. Only those 65 or older, those with an “altered” immune system or with small children, would be eligible to work from home. Decisions would be made case by case.

Mack had a key COVID-19 risk factor, obesity. But even after the intervention of Anthony Smith, president of her union chapter, management refused to approve Mack’s request for telework.

The decision put Mack in the office on Candace Young’s last day there.

Young, 31, now suspects she was unknowingly spreading the coronavirus. She said she has “no doubt in my mind” she contracted it on the job from a client or co-worker; work was the only place she came into contact with anyone outside her household. Young avoided even the grocery store because her pregnancy was high-risk.

At the time, the department “didn’t take any mitigation measures in terms of limiting contact between employees,” Smith said. “They were very spotty with their PPE.”

That day — Thursday, March 19 — proved fateful.

Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan announced he was ordering government buildings to post recommendations about social distancing, and he banned social and community gatherings of more than 10 people.

Young, who like the other specialists worked in a cubicle, mingled with co-workers as usual. She, Mack and some 20 others were called to a routine staff meeting, where they sat in a U shape. Someone mentioned the paradox of recommending social distancing in the community while sitting much less than six feet apart, Young recalled.

Later, union documents show, nine of 19 disease intervention specialists in family health services, at least some of whom attended the meeting, tested positive for COVID-19.

Virus Takes Its Toll

Young noticed mild symptoms the next day and felt worse over the weekend. She said she notified her supervisors on March 24. Two days later, she became the first in the program to be diagnosed with COVID-19.

A day after her diagnosis, her colleagues received texts and calls saying they had been exposed to an employee who tested positive, a union report says. All of them would be quarantined at home, including Mack. Young began recovering only after giving birth by cesarean section on April 2. Her 5-pound, 9-ounce daughter tested negative.

Mack, who knew about Young’s illness, began feeling sick and got tested for the coronavirus in early April.

On April 4, in a department memo obtained by KHN, health officer Carter said additional staff members had contracted the virus or reported illness.

Mack was one of at least four employees who union officials say were hospitalized. She entered Adventist HealthCare White Oak Medical Center in mid-April. She stayed on a ventilator for four weeks. She needed a blood transfusion. Her kidneys failed. She developed a brain bleed.

On May 11, Mack’s heart stopped, and she slipped away.

“She was a good soul — strong,” said her brother. “It’s so messed up.”

“Just not having my sister around no more, it’s going to be a tough one,” says Roland Mack, at home in District Heights, Maryland, on June 19, in front of photos of his sister, Chantee Mack, who died of COVID-19.(AP Photo/Federica Narancio)

A Terrible Price

Three employees who worked at Oregon’s Multnomah County Health Department also contracted the virus. In Ohio, it struck workers at the Toledo-Lucas County Health Department, forcing the community’s main COVID-19 response team into quarantine. Some of the staffers continued to work through their illnesses while in isolation, though, because the county’s caseload was still growing.

In California’s Coachella Valley, Fernando Fregoso, 52, died of COVID-19 and three colleagues in the local mosquito control district later tested positive. The district — which had already put in place safety measures such as social distancing — shut down for two weeks.

In the wake of Mack’s death in Prince George’s, union leaders said the health department has stepped up its workplace COVID-19 protections, as have other departments. By mid-June, employees in Mack’s division who had been teleworking had returned to working some days in the office.

“The health and safety of our employees is our top priority,” Carter’s statement said, adding that all employees must wear protective equipment at work, stay six feet from others and wash their hands. Those working with clients must take even more precautions.

“I do believe we’re making progress,” Smith said. “But we’ve paid the price.”

Mack’s brother said his family has been devastated.

“I feel alone now that she’s gone,” he said. “From the time I was 5 years old, she was taking care of me like a second mom.”

Before Mack died, her brother said, she’d begun to talk about moving on from the health department. She wanted to make good on a long-held dream — following their late mother, the woman she considered her best friend, into nursing.

Instead, the two are buried side by side.

KHN Midwest correspondent Lauren Weber, senior correspondent Anna Maria Barry-Jester and data reporter Hannah Recht contributed to this story.

This story is a collaboration between The Associated Press and KHN.