By the mid-1970s, India’s smallpox eradication campaign had been grinding for over a decade. But the virus was still spreading beyond control. It was time to take a new, more targeted approach.

This strategy was called “search and containment.” Teams of eradication workers visited communities across India to track down active cases of smallpox. Whenever they found a case, health workers would isolate the infected person then vaccinate anyone that individual might have come in contact with.

Search and containment looked great on paper. Implementing it on the ground took the leadership of someone who knew the ins and outs of public health in India.

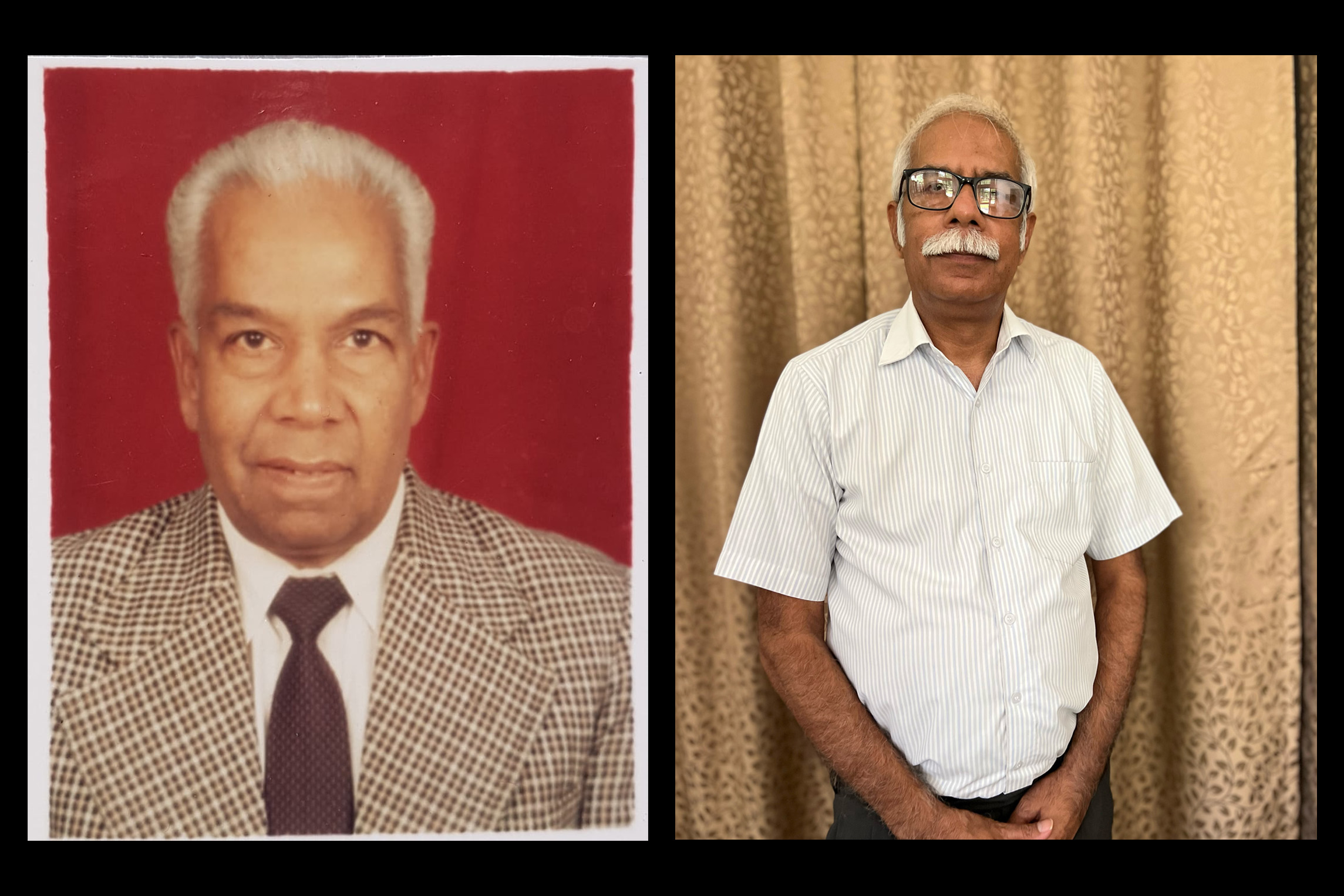

Episode 2 of “Eradicating Smallpox” tells the story of Mahendra Dutta, an Indian physician and public health worker who used his political savvy and local knowledge to pave the way to eradication. Dutta’s contributions were vital to the eradication campaign, but his story has rarely been told outside India. To conclude the episode, host Céline Gounder and epidemiologist Madhukar Pai discuss “decolonizing public health,” a movement to put leaders from the most affected communities in the driver’s seat to make decisions about global health.

The Host:

In Conversation With Céline Gounder:

Voices From the Episode:

Podcast Transcript

Epidemic: “Eradicating Smallpox”

Season 2, Episode 2: Do You Know Dutta?

Air date: Aug. 1, 2023

Editor’s note: If you are able, we encourage you to listen to the audio of “Epidemic,” which includes emotion and emphasis not found in the transcript. This transcript, generated using transcription software, has been edited for style and clarity. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

TRANSCRIPT

Céline Gounder:

This season, the “Epidemic” podcast is about the eradication of smallpox in South Asia. And to understand the breakout public health strategy that ultimately made eradication possible, we’re taking a quick detour … to West Africa.

[Nigerian music begins to play.]

Céline Gounder:

It was 1966 — and Bill Foege found himself in Nigeria. The young physician and epidemiologist from Iowa was a long way from home — but in good company as part of a team of health workers sent to the region by the CDC [the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]. Their mission was to vaccinate as many people as possible to stop smallpox.

They traveled from one remote location to the next on electric bikes. [Electric bikes whir.] To coordinate the work and respond quickly to each new outbreak, they had two-way radios. [Radio static crackles.]

[Music fades to silence.]

Bill Foege:

On Dec. 4, 1966, I got a message saying, “I think we have smallpox. Could you come and look?”

We went to the place, 8 miles off of a road, and it was immediately clear that the first person I saw had smallpox. And so, we started looking at: What did we have in the way of vaccine?

Ordinarily, you would’ve done a mass vaccination campaign around the area.

Céline Gounder:

At the time, the standard procedure was to vaccinate every single person in the region. But there was a problem: There wasn’t enough vaccine. Bill was still waiting on a big shipment. Without enough doses to vaccinate everyone, his team had to break protocol and get creative.

Bill Foege:

We knew what we should do, but we couldn’t. So, at 7 o’clock that night, with maps in front of me, I divided the area and sent runners to the villages to see if they had smallpox. Twenty-four hours later, we got back on the radio [radio static], and now I could pinpoint the exact villages where there was smallpox. And we used the rest of our vaccine on those areas.

[Music begins.]

Bill Foege:

Much to our surprise, smallpox simply stopped in weeks. We just were so fortunate — so lucky that with our limited vaccine, we were able to hit the right people. And by July, we were working on the last outbreak in all of eastern Nigeria.

Céline Gounder:

The health workers began to wonder: Could this approach also work in other parts of the world?

The new vaccine strategy — the innovation that Bill and his team stumbled upon, out of necessity — came to be known as “search and containment.”

That meant …

First searching for anyone with an active case of smallpox.

Then isolating the infected person.

And finally, tracking down and vaccinating everyone that person had come into contact with.

It worked in West Africa. Could it work in South Asia?

[Music fades to silence.]

Céline Gounder:

Getting locals there to adopt search and containment was going to take an ally, a leader with a big personality who knew the ins and outs of public health in India. Someone who could make things happen. Someone whose story you’ve probably never heard.

Yogesh Parashar:

Things look very rosy and very nice in a textbook. You never get the feel of what actually happened, how much sweat it entailed, what blood it entailed.

Céline Gounder:

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder and this is “Epidemic.”

[“Epidemic” theme music plays then fades to silence.]

[Music begins.]

Céline Gounder:

By 1973, countries from Nigeria to Brazil to Indonesia had recorded their final cases of smallpox. But in India, the campaign to end the disease was still grinding along. The population was roughly 600 million people — and the goal to vaccinate every single person in the country was daunting.

Epidemiologist Bill Foege was older now — in his late 30s — and leading the CDC’s global program to eradicate smallpox.

He turned his attention to Bihar, a state in eastern India. It was the biggest smallpox hot spot in the world. There, Bill found an ally and a good friend in another physician, a man named Mahendra Dutta. Mahendra was in charge of the smallpox eradication program in Bihar.

[Music fades to silence.]

Yogesh Parashar:

He had a booming, loud voice.

Céline Gounder:

That’s his son Yogesh Parashar, a pediatrician living in Delhi.

Yogesh Parashar:

My father was known for his honesty. He would help people. He had that nature.

Céline Gounder:

Mahendra Dutta died a few years ago. And Yogesh was just a boy during the eradication campaign. But his father shared stories from his years in the trenches fighting smallpox. And there was no battle bigger — or more lifesaving — than persuading the vaccinators to change their way of doing things.

After a decade of mass vaccination, smallpox raged on. Yogesh says his father could see that the strategy wasn’t working quickly enough to stop the virus.

Yogesh Parashar:

The standard way of doing things is not going to get us anywhere. Being nice, doing the right way, is not going to get the disease away.

Céline Gounder:

It was time to try something new. But getting India to adopt search and containment would prove challenging.

Yogesh Parashar:

People who were trained in the previous school of thought could never believe that smallpox could be got rid of in this strategy.

Céline Gounder:

Luckily, Mahendra could be very persuasive.

Yogesh Parashar:

My father did all the dirty work. He got enemies also in the process, I’m sure he did, but that is what he did.

[Music begins.]

Céline Gounder:

Mahendra Dutta was a gifted political strategist who built relationships with magistrates and commissioners throughout his work in public health. He was an insider who moved comfortably through the halls of power in India.

Once, over dinner and a glass of whisky — Chivas Regal, to be specific — a senior official told Mahendra to come to him in the future if he ever needed a favor. Later, when it was time to build support for search and containment, Mahendra knew exactly how to cash in on that promise.

Yogesh Parashar:

My father gifted him the Chivas Regal.

“Now do you remember? You had told me that if I need any help, I should come to you. And here I am asking for help now.” This is how he did it.

Céline Gounder:

You might call it “Dutta diplomacy.”

[Music fades to silence.]

Céline Gounder:

Using charm and his extensive personal network, Mahendra recruited a staff of workers dedicated to the new strategy of search and containment — instead of trying to change the minds of people invested in the old ways of doing things.

Yogesh Parashar:

So, practically, a parallel health system was set up.

Céline Gounder:

The stakes were high.

Yogesh Parashar:

Any outbreak was an emergency, because if you don’t move within hours and contain it, you do not know how many contacts will be there, how much it would spread, and your work would increase exponentially.

[Suspenseful music begins.]

Céline Gounder:

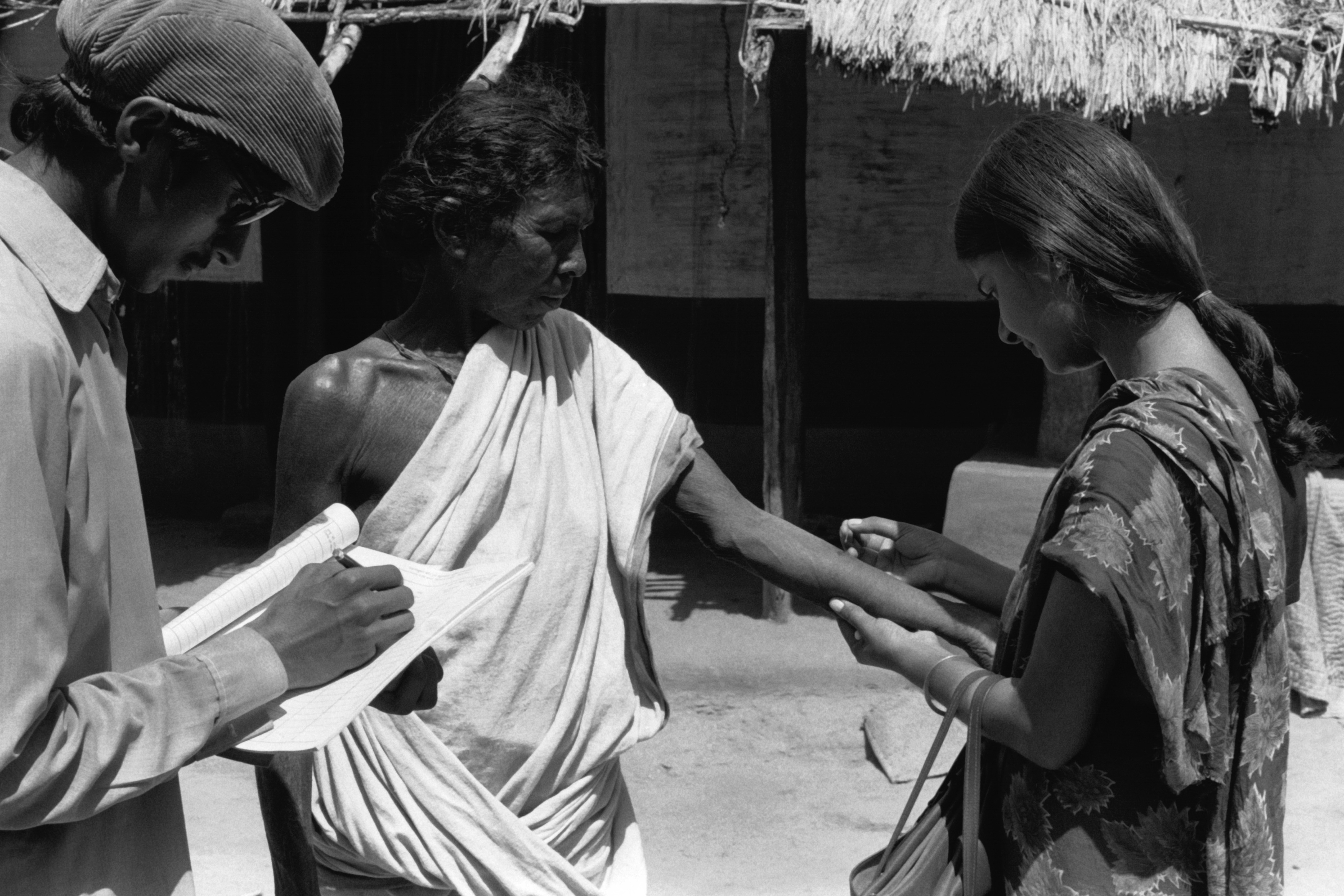

Instead of waiting for smallpox cases to be reported, the workers headed out into the community to look for them.

Bill Foege:

At first, we went and we talked to the village headmen, the teachers, and some children. And gradually, we went from that to actually going house by house in every village.

Céline Gounder:

But some cases were still falling through the cracks.

Bill Foege:

And so, we developed secondary surveillance teams who would go around to the markets with a smallpox identification card.

Yogesh Parashar:

There were WHO [World Health Organization] cards, which had photographs of cases of smallpox, their face, their body, and so on. So, the people would go out and ask the students, ask the people in the market, “Have you seen such a person with this kind of an illness?” This was one way of actively searching.

Céline Gounder:

Everyone was willing to help.

Yogesh Parashar:

The vehicle driver would also ask. Why would the foreign epidemiologist ask? The vehicle driver will talk in the local language: “OK, I’m looking for this.” They will tell him, “Yes, this is here.”

Céline Gounder:

And, as soon as a case was identified, a team of containment workers would spring into action, isolating the patient, tracking down their recent contacts, and vaccinating anyone they could have transmitted the virus to.

[Suspenseful music fades to silence.]

Céline Gounder:

By 1974, the scale of the smallpox surveillance operation was gigantic. Over 100 million households across India were visited every single month in the search for active cases. Over 130,000 field workers were mobilized.

Bill Foege:

At that point, we were having 1,500 new cases of smallpox a day in Bihar.

Céline Gounder:

To manage all these moving pieces, the workers documented their efforts meticulously.

Bill Foege:

I mean, you can’t imagine the millions of forms that we had. We had forms for everything. Forms for the containment team, forms for the assessors, forms for the watch guards.

I often said, “We’ve just buried smallpox in forms.”

Céline Gounder:

Search and containment was working in Bihar. Mahendra and Bill could finally see a path to eradication.

Then, they hit a very public stumbling block that threatened to derail their work.

[Sound of bomb exploding.]

Céline Gounder:

In May 1974, journalists from all over the world flooded into the country to cover a major news event.

Here are a few lines from a New York Times article from that time.

[Voice actor reading a headline from the May 20, 1974, edition of The New York Times. An audio filter gives it a grainy ’70s newscaster’s sound. Typewriter sound effects play.]

Newscaster:

India conducted today her first successful test of a powerful nuclear device. The surprise announcement means that India is the sixth nation to have exploded a nuclear device.

Céline Gounder:

The code name for the nuclear bomb test was Operation Smiling Buddha. And with it, the country joined a short list of superpowers. All eyes were on India.

[Dramatic music begins playing.]

Céline Gounder:

And … those international journalists on the hunt for interesting things to report came across another big story: Smallpox cases appeared to be exploding.

Bill Foege:

And then suddenly the newspaper articles come out saying, here’s India working on nuclear weapons and they can’t even control smallpox.

Céline Gounder:

In actuality, the new search-and-containment strategy was just a lot better at uncovering cases of smallpox.

But those glaring headlines — accurate or not — put the eradication program in the spotlight.

[Dramatic music fades to silence.]

Céline Gounder:

Indian health officials were worried. And they threatened to pull their support for search and containment.

The famous Dutta diplomacy was about to be put to the test …

Bill Foege:

The minister of health for all of India came to Patna, and Mahendra Dutta went to the airport to meet him.

Yogesh Parashar:

He said, “I have to address a meeting, and it would be difficult to talk to you separately. So why don’t you get into my car?”

Céline Gounder:

During the ride, the minister of health told Mahendra that he was on his way to a press conference to announce that the smallpox program would switch back to the strategy of mass vaccination.

To Mahendra, giving up on search and containment meant giving up on their best shot at eradication.

Bill Foege:

And that’s when Mahendra Dutta said, “Before you do that, you have one more thing to do.” And he said, “What’s that?” He said, “You have to fire me.”

Yogesh Parashar:

My father tells the minister that “if we are going to follow vaccinating everyone, then I think I should give you my resignation.”

Bill Foege:

And the minister was irate. He said, “Do you know who you’re talking to?” And he said, “I do. And that’s how important this is.”

Céline Gounder:

Mahendra told him the latest figures. He explained how the team was finally slowing the virus — that things were coming under control.

And the health minister listened.

Yogesh Parashar:

And, within a few minutes, when they had reached the venue, the health minister was addressing the other officials, and he said, “OK, we have a new strategy of search and containment, which is very successful, has been tried in a number of countries, and we will bring forward this strategy and get rid of the disease.”

[Triumphant music begins playing.]

Bill Foege:

All he did was praise the smallpox workers for what they had done, never said a word about switching back to mass vaccination.

That’s how close we came, I think, to losing the program in India. And, of course, if we lost it in India, we lost it everyplace.

Céline Gounder:

If India, with its population of over 600 million people, failed to stop smallpox, then the virus would have remained a threat to the entire world.

Yogesh Parashar:

My father has done the dirty job of saying what is to be said and got away with it.

He diplomatically bought time, allowed the search and containment to go on and get “smallpox zero.”

[Triumphant music fades to silence.]

Céline Gounder:

While some of his American collaborators have been celebrated around the world for their work to end smallpox, Mahendra Dutta’s story — and his contributions — aren’t well known outside of India.

But we managed to find this recording of his voice …

[Brief pause.]

Mahendra Dutta:

In public health, community approach, your conviction, your devotion, and team effort, that’s what matters the most.

Céline Gounder:

That’s Mahendra Dutta in 2008, when he was in his late 70s. He and Bill Foege sat down together to reminisce about the history of smallpox eradication as part of a CDC event.

The two old friends reflected on what they’d learned together.

Bill Foege:

I think that’s the lesson of smallpox in India, that the team worked as a unit. It was a coalition in truth.

Mahendra Dutta:

Devoted efforts, team efforts always matter in community health work.

[Music begins playing.]

Céline Gounder:

Search and containment was one of the public health innovations that made eradication possible — that, and the collaboration among international health workers and local public health leaders.

Here, we followed the story of Mahendra Dutta, but there were many names — thousands — working together toward a common goal.

[Music begins.]

Céline Gounder:

I have a friend who thinks about that a lot. Madhukar Pai is a community medicine physician, an epidemiologist — and he teaches global health.

His big thing is he wants rich countries to stop trying to use their own lens to solve health problems around the world. He says that just doesn’t work.

He’s calling for a “radical shift.” But …

Madhu Pai:

It is hard to give up on power and privilege. No powerful person wants to ever give it up.

Céline Gounder:

More from Madhu after the break.

[Music fades to silence.]

Céline Gounder:

Wiping out smallpox nearly 50 years ago required the skill of thousands of local people who are largely unrecognized in any history book — or podcast.

Putting locals in the driver’s seat is one part of a growing movement to “decolonize” public health.

That term might sound wonky. But Madhukar Pai, a professor of epidemiology and global health at McGill University [in Montreal], says decolonizing public health is exactly what’s needed to get to health equity around the world.

But Madhu is frankly pretty pessimistic about the current system.

Madhu Pai:

I sometimes wonder how the hell did we eradicate smallpox. I mean, today, I don’t think we would have. Honestly, if there was a virus like smallpox today, there’s zero chance of eradicating it.

Céline Gounder:

So what was it about smallpox eradication that allowed us to do it?

Madhu Pai:

I think those were simpler days, right? And then WHO said, you know what? Let’s just get all together and just help end this disease. That collaboration was unprecedented in smallpox.

But I think it was, in the end, remarkable numbers of people, you know, essentially armies of community health workers, vaccinators, front-line staff, field workers. And that was a mobilization kind of an effort that I think we definitely tried to do during covid. But probably not as unified as we could have been.

Céline Gounder:

We did try to do something like that. It was called COVAX.

It was an alphabet soup of international groups — from Gavi to the WHO — that wanted to pool buying power and scientific resources.

COVAX was an attempt to make sure that there was covid vaccine for the whole world.

So … why did COVAX fail?

Madhu Pai:

First of all, I think COVAX was conceived by “global north” white people, and it was conceived with all good intent, but essentially the “global south” was left behind even in the design of COVAX. Now that in essence is global health, right? That is, privileged people in the global north are constantly making decisions, thinking that we know best.

Céline Gounder:

In case our audience isn’t familiar with that term, when Madhu says “global north,” that’s a shorthand for talking about wealthy industrialized nations.

Madhu Pai:

Relying on the global north time and time and time again is doomed as an idea because we’ve seen there is no end to our greed and myopia and self-centeredness.

Céline Gounder:

What would that have looked like? Centering international efforts to provide vaccines to low-income countries?

Madhu Pai:

To me, centering on them rather than us and saying, “What do you need from us to succeed in your plan?” Right? “How can we be allies to you?” We need to get behind that and respect the desires and the aspirations of global south countries.

If there is a new pandemic and there’s a new vaccine or medicine, that technology should be transferred very quickly.

That’s what allyship genuinely is about. And that’s what our country should have done. We could … should have been allies as countries, right? We should have given the vaccine recipe. We should have helped out way better with the vaccine donation — the opportunity of a lifetime to be good allies. But we left it on the table.

Céline Gounder:

If you had to give a grade to our global health response to covid, what would it be and why?

Madhu Pai:

I would probably give it a “D” because I think, as humankind, we genuinely failed. There’s no reason at all so many people should have died. That’s inexcusable. The fact that 2.3 billion people, mostly in low-income countries, middle-income countries have not received even one dose is a very telling statement on how this all unfolded. That’s political failure. It’s got nothing to do with science, technology, or availability, or money.

Céline Gounder:

So let’s say another pandemic hits us tomorrow. How is that gonna play out, then?

Madhu Pai:

Exactly like it played out in covid, I do not expect anything different, honestly. Which is bloody sad, really.

Céline Gounder:

You said before that the big global health programs have good intentions. So, what should they be doing differently?

Madhu Pai:

Global health, as you know, is full of these examples where the global north person always gets the, you know, the shining credit and the medal on the wall.

We need to kind of flip the switch and re-center global health away from this, what I call default settings in global health, to the front lines. Right? People on the ground. People who are Black, Indigenous. People who are in communities. People who are actually dealing with the disease burden. People who are dying of it, right? People who have actually lived experience of these diseases that we are talking about, right? Having them run it is the most radical way of reimagining and shifting power and global health.

Céline Gounder:

As Madhu and I were talking, he reminded me about Bill Foege. He’s the American eradication worker from Iowa we already met in this episode. The one who worked closely with local partners like Mahendra Dutta.

But near the end … he stepped out of the spotlight.

I asked Bill about this:

Céline Gounder:

You left India before smallpox was declared eradicated. And as I

understand it, that was important to you to no longer be in the country at the time. Why is that?

Bill Foege:

I had the feeling that it should be an Indian victory. That foreigners should be happy and pleased that they had a chance to be part of it but don’t get carried away with being celebrated.

Madhu Pai:

People like Foege are the exception in global health and not the norm. Finding ways to completely disappear and then center on people who really matter, I think is a, is a great gift.

The ability to do Dr. Foege’s ego-suppression work, uh, allyship work, that’s where the next frontier lies. And I’m not sure if we are ready for it, right? Because it is hard to give up on power and privilege, right? No powerful person ever wants to give it up.

Céline Gounder:

So if you had a call to arms to your colleagues about preparing for the next pandemic, what would you say?

Madhu Pai:

Yeah, I would say, anything that is led by global south, anything that is led by communities, must be on top of the agenda because that is how this is all gonna work.

So I don’t think climate change, or conflicts, or covid will be magically solved by global north institutions or individuals. So, de-center, de-center, de-center away from us, and be good allies to the global south.

Everybody’s agreed that we gotta do better, you know, we’ve got to decolonize global health. But it isn’t meaningfully moving the needle in the right direction. Because when rubber hits the road, our allyship only goes so far as just talking about it, which is not allyship at all in the first place.

[“Epidemic” theme music begins playing.]

Next time on “Epidemic” …

Bhakti Dastane:

We have to achieve “zeropox,” so it was our motto: “zeropox.”

CREDITS

Céline Gounder:

“Eradicating Smallpox,” our latest season of “Epidemic,” is a co-production of KFF Health News and Just Human Productions.

Additional support provided by the Sloan Foundation.

This episode was produced by Taylor Cook, Zach Dyer, Jenny Gold, and me.

Our translator and local reporting partner in India was Swagata Yadavar.

Taunya English is our managing editor.

Oona Tempest is our graphics and photo editor.

The show was engineered by Justin Gerrish.

We had extra support from Viki Merrick.

Music in this episode is from the Blue Dot Sessions and Soundstripe.

Audio of Mahendra Dutta via the Global Health Chronicles recorded at the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

If you enjoyed the show, please tell a friend. And leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find the show.

Follow KFF Health News on Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok.

And find me on Twitter @celinegounder. On our socials, there’s more about the ideas we’re exploring on the podcasts.

And subscribe to our newsletters at KFFHealthNews.org so you’ll never miss what’s new and important in American health care, health policy, and public health news.

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder. Thanks for listening to “Epidemic.”

[“Epidemic” theme music fades to silence.]

Bill Foege:

It was great to work with you then, and it’s great to hear you reminisce now.

Mahendra Dutta:

I’m also pleased that I’d worked with you.

Credits

Additional Newsroom Support

Lydia Zuraw, digital producer

Tarena Lofton, audience engagement producer

Hannah Norman, visual producer and visual reporter

Simone Popperl, broadcast editor

Chaseedaw Giles, social media manager

Mary Agnes Carey, partnerships editor

Damon Darlin, executive editor

Terry Byrne, copy chief

Gabe Brison-Trezise, deputy copy chief

Chris Lee, senior communications officer

Additional Reporting Support

Swagata Yadavar, translator and local reporting partner in India

Redwan Ahmed, translator and local reporting partner in Bangladesh

Epidemic is a co-production of KFF Health News and Just Human Productions.

To hear other KFF Health News podcasts, click here. Subscribe to Epidemic on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.