Ruth Titus, a 59-year-old cook from Taos, N.M., leaped at the opportunity in July to sign up for health insurance under a new federally subsidized program for uninsured people with health problems. With her history of bladder cancer, she said “it was hopeless to even look” for private coverage because she’d be turned down.

Titus is one of what some officials say has been an unexpectedly small number of people to sign up for the program, which was touted by the Obama administration as an early benefit of the new health overhaul law. It began last month in 30 states with the expectation that many thousands of uninsured people would apply for the opportunity to get comprehensive coverage regardless of their health status. But that hasn’t been the case.

About 3,600 people have applied and about 1,200 have been approved so far in state plans that started in the beginning of July, according to data from the states and federal government. Officials say the new plans, although a better deal than anything comparable on the private market, still may be unaffordable for many people. Eligibility requirements are another possible barrier. And states have had little time to publicize the plans.

It’s too soon to gauge the program’s impact. The plans won’t be up and running in all the states until September. But some officials are surprised.

“It’s early, but thus far interest in the program is lower than we expected,” said Michael Keough, executive director of the North Carolina Health Insurance Risk Pool, which started July 1. As of Tuesday, 314 people had applied and 158 had been approved.

GettingUSCovered, Colorado’s program, has received 204 applications; 108 people are enrolled. It’s a “very low number given that there are hundreds of thousands of uninsured in the state,” said Suzanne Bragg-Gamble, the executive director.

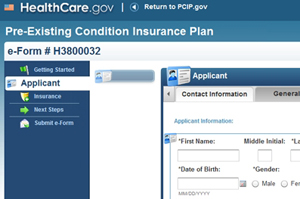

Many states were so worried about not being able to meet the demand for coverage with limited federal funding that 22 of them deferred to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to run the new plans as part of the Pre-Existing Condition Insurance Plan program. The other 28 states and the District of Columbia opted to start their own.

Questions About Affordability

Enrollees must pay premiums for their coverage, which is comprehensive and doesn’t exclude any pre-existing conditions. But the federal government is subsidizing the program with $5 billion until 2014 when the program ends because insurers will no longer be able to discriminate based on a person’s health status. Some analysts had predicted the money would run out before then, leaving states on the hook to help fund the plans or limit enrollment and benefits.

“It is certainly possible that the market for this coverage is smaller than everyone anticipated,” said Mark Merlis, a consultant who wrote a report on the program for the Center for Studying Health System Change, a Washington group. But he said even with lower than expected enrollment the program may exhaust its funds because only the sickest people will join.

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that as many as four million uninsured Americans would be eligible and that 200,000 would actually be enrolled by 2013. That projection assumed some people would not be interested or would not be able to afford the premiums.

The new plans are seen as a big improvement over existing “high-risk” programs in many states that provide an option to people who have difficulty getting insurance but often at a very high cost and after long waiting periods.

Not everyone can afford the premiums of the new plans, which are cheaper than the existing high-risk programs. Federal regulations prohibit the new plans from charging more when people have health problems.

Premiums vary from plan to plan and are affected by the age of applicants, where they live and whether they smoke. For example, the monthly premium for a person aged 45 to 54 who does not smoke ranges from $330 in Hawaii to $556 in Florida, according to HHS. And prices can vary within a state: A 50-year-old non-smoker in Denver would pay $397 a month with a $2,500 deductible; a 40-year-old would pay $275 a month.

Titus pays $251 month for her policy, which includes a $2,000 deductible. “It was a huge relief,” she said after obtaining coverage. “Even though it’s expensive it is nothing like trying to pay out of pocket for every day in the hospital.”

Applicants may also be put off by eligibility criteria. They must have been uninsured for at least six months and have a pre-existing condition. In addition, they must prove they’ve been rejected for coverage by a private insurer within the past six months or been denied coverage for certain benefits. More than a dozen states also give applicants the option to provide a doctor’s note as proof they have a pre-existing condition such as cancer or rheumatoid arthritis, which is how Titus got coverage.

Officials with the state plans also point to a lack of publicity. Government Employees Health Association, the Kansas City company that has the federal contract to run the plans in 22 states, said it hasn’t yet started a major marketing campaign.

HHS is trying to get word out, says spokeswoman Jessica Santillo. “HHS has been working with states, consumer groups, insurance companies and other partners to reach uninsured individuals with pre-existing conditions who may be eligible,” she said.

In the 22 states where the plans are run by the federal government, a total of 2,400 people have applied as of Aug. 13, according to HHS, which would not release numbers for each state because it said they’re “fluid.”

Application numbers vary considerably in other states that launched their own plans July 1: Montana (100); New Hampshire (12); New Mexico (82), Oregon (400) and South Dakota (31). Connecticut could not provide an applicant total but said one person had been enrolled as of last week.

Kim and Eddy Graham of Belen, N.M., are among those who have enrolled. They previously were uninsured. Both have hepatitis C, among other problems. Now, for the $370 a month the couple pays for coverage, Kim Graham, 50, says she’s been able to get physical therapy and acupuncture for her bad back and saves money on medicine. “I love this program,” she said.

This story was corrected from an earlier version.